This is the second instalment in a series of articles that could have been called “What Is Wrong With Current Video Games”, “Where Did the Video Game Industry Turn Wrong”, or something to that effect. In the first, “Inhuman Rights“, I argued that one of the biggest problems of current computer and video games is the stagnated or even devolved state of Artificial Intelligence in games. In this one I will argue that an ever-increasing focus on visual presentation is hollowing other aspects of the game, the very aspects that, unlike graphics, constitute the game play itself, the “contents” if you wish, of a game.

To start out, it is utterly indisputable and uncontroversial that the visual presentation (i.e. the “graphics”) has become the most important game play aspect: a disproportional portion of game development budget is spent on it; graphics is always a primary focus of game reviews; a significant amount of talk and buzz on fora etc are about it; etc. In a way, visual excellence is equated with enjoyment. Much less conceptual space is placed on story, game play, believability, creativity, or even sheer fun, and games today, compared to games of a decade ago, generally have less developed story and narrative: their interfaces are less interactive and more coldly order-oriented; and feedback from the game is more informative than attempting to establish a relationship with the player. So, what has led to this? Let’s start by stating some immediately observable facts, or at least facts that are obvious with some reflection and reminiscence:

| Already the old Geek, back in 1983, saw this coming: |

|

| “Spike’s Peak features multiple stages and high resolution graphics. It’s a shame that its gameplay sucks so bad.” (http://www.videogamecritic.net/2600ss.htm) |

First of all, graphics capabilities have escalated at a tremendous rate, if only evolutionary. Though the common argument would be that the demands of gamers and the game industry drives the development of graphics performance, in actuality the relationship is much more reciprocal: Increased graphical capabilities presses developers to constantly upgrade to “not fall behind”. Thus, the hardware industry do have some blame by pushing the always more potent graphical crack.

Secondly, it is very noteworthy that with the graphics revolution we’re experienced an accompanying shift, or increased focus, or game genres, especially for the PC platform. Most games tend to be variants of first-person shooters, real-time strategy (of the more-or-less conventional type, as contrasted to f.i. real-time tactics), or other action-oriented stereotypes. Though not an a priori predetermined consequence of increasing graphical capabilities, narrative games, adventure games, or other games of slower pace or cerebral nature have virtually disappeared.

That contemporary media, not games but also movies and music, is of intellectually attenuated and increasingly formalistic and mass-produced contents, too, is not really controversial. In fact, rather than denied, it is popularly, almost reflexively, attributed to a generational shift in attention span and lessening abilities to deeply concentrate. For instance, in 2002 Professor Greg M. Smith of Georgia State University said in a Gamestudios article said:

Although dialogue conventions have been developed in the novel and the theater, those conventions have been compressed in current film and television practices. Whether or not one blames the postmodern condition of interrupted sensibility or the economic pressure to maintain a declining viewership, contemporary media have taught audiences to read the narrative function of dialogue cues very quickly.

Or in other words, increasing superficiality is reflected in media. Speaking of the increasing importance, however, his claim is that computer games are a “primarily visual media”:

Since most people think of computer games as a visual medium, the primary faith in the evolution of games resides in improving the technology for their visual presentation. As designers are able to render more and more polygons, they can depict facial details more precisely, making more naturalistic expression and more nuanced characters possible. Assumedly, denser visual information will give the digital spaces explored by the interactive player some of the richness of the cinematic signifier. As long as we consider games to be primarily visual, it makes sense for both designers looking to shape the future and for critics wanting to explain present games to concentrate on the visual expressivity of this young medium.

That computer games are primarily a visual media (though not exclusively) is a claim with some merit, albeit perhaps not to exclusion, though consumers are increasingly brainwashed with the notion. Nonetheless, it is not an answer to what has caused the situation we see today with increasingly superficial “looker” games. Painted art is to an even higher extent a visual media, and if visual perfection was the goal of painting then artists would still only produce photorealistic landscapes. On the other hand, if computer graphics, too, had been perfected in the 17th century perhaps we’d have surrealistic modern art computer games today. Thus, games might be undergoing a phase where its visual component matures and eventually stabilised, whereafter attention will again be directed toward other dimensia. At the moment, however, the general agreement seems to be that “better graphics is better period” (interesting enough, some talk about too good graphics becoming “uncanny” and off-putting).

The Economics of Graphics

Contrafactual speculations about historical projections aside, we’re still just as caught with resplendently stupid games in increasing amounts. In the end, this is very likely due to a simple relationship: graphics costs money. 3D costs more than 2D, and sophisticated 3D costs more than simple. The game industry is getting huge, and with demand and market, so does the number of released games. With more titles out the market noise increase, and so the need to stand out. In what is perceived as a “primarily visual media” you stand out with better graphics and bigger games (note “bigger”, not necessarily “better”). Better graphics and bigger games cost more money (more modellers, artists, level designers, etc), and games get more expensive. Expensive games requires financing, and investors want returns. Investors abhor uncertainties and prefers proven formulas (not only in games, but in movies and music, and everywhere). Proven formulas are what’s already successful: FPS, RTS and action games with improved graphics. With increasing competition and budgets, risk-avoiding behaviour increase. A perfectly vicious little circle and a Catch 22 for other contents as more and more is focused on graphics.

Related to this, it is a very sad fact that more and more games are released in a quite “unfinished” state, relying on post-release patches to “finish up” the title. After having partaken in several beta tests I have, as a computer games designer and programmer, come to the conclusion that games very often seemed designed around the graphics, rather than the game mechanics, and patches try to retrofit post-release what should have been fundamental functionality at the very project onset. A conclusion from this, though perhaps “diagnosis” might be a better word, is that “graphics” has moved from being a conceptual focus to a conceptual pathology among developers; pathological in that it is a “deviation from a healthy, normal, or efficient condition” (the Unabridged Dictionary), or “the anatomic or functional manifestations of a disease” (Stedman’s Medical Dictionary).

Effects on Game Development and Evolution

In sum, what are the effects? Graphics cost money, which means smaller developers, which are generally more imaginative or innovative, can’t compete unless funded externally. Investors don’t take changes, demand rights of intervention, and direct the projects in “more appropriate” directions. If the games are successes, they were proven right, if it fails, they see deviating from the pure formula as the culprit – similar to dogs that know that it is their barking that drives away the garbage collectors. With the same soup being serves, discriminate gamers stop consuming (dropping into other hobbies, or playing retrogames on their emulators) and new gamers are formatted to the new standard. The market is streamlines and games are intellectually devolved further and we get more of the same excrement, only prettier. Pretty or not, it still taste pretty bad.

In conclusion

Graphics is a vicious circle. Nintendo Wii is the first large-scale industrial (that is, non-indie) actor that has tries to break out of it, and I applaud them! DRM-crazed or not, Nintendo has always placed quality of games above mere visuals, and by not going for cutting-edge hardware their new platform is cheap compared to the competition. Though innovative, the controllers are already plagiarised by Sony and Microsoft (which of course claims to “have independently had them in development” for a long time), so they won’t have the same effect. Nintendo attempts to compete solely on the grounds of quality of games. Nonetheless, frustratingly enough it might be a big mistake. After the DVD becoming mainstream “graphical awareness” has crept into population at large, and Wii’s “impoverished” graphics and no HD might make an uninformed mainstream ruminating on popular “knowledge” disregard it.

I remain a cynic.

Mind Control Software’s‘ Oasis, situated in ancient Egypt, is what you get if you take the archetypal turn-based strategy (“TBS”) titles like Civilization, keep all its concepts -exploration, cities, armies, technology research, roads- and boil it down to its monofilament skeleton. You explore the map (all of which fits on screen at once) find cities, workers, and mines by clicking on fog of war; you spend workers on building roads and researching technology (by clicking on land or mines); mines automatically generate technology, cities automatically grow when connected by roads; and after a given number of turns barbarians attack and you’d better be ready. There is no widget-interface, everything is done by left-clicking map tiles. It is everything you find in TBS games, contained in one screen and condensed playing time. It is easy to learn, entertaining to play, and beautifully executed. If you like the concept of Civilization but, like me, are loath to spend 15 hours or more on a game, then this may be for you. However, its strengths -tight focus and constrained game play freedom- are also its weaknesses: it gets “understood” fast and is quite repetitive. Technology comes in predetermined order, and due to the tightly defined game play, all games play out similarly. After the first hour, the game does not surprise you any more, but nonetheless, it is still enjoyable. Also, every game developer should study this game and so gain a better understanding of the mechanics of TBS games!

Mind Control Software’s‘ Oasis, situated in ancient Egypt, is what you get if you take the archetypal turn-based strategy (“TBS”) titles like Civilization, keep all its concepts -exploration, cities, armies, technology research, roads- and boil it down to its monofilament skeleton. You explore the map (all of which fits on screen at once) find cities, workers, and mines by clicking on fog of war; you spend workers on building roads and researching technology (by clicking on land or mines); mines automatically generate technology, cities automatically grow when connected by roads; and after a given number of turns barbarians attack and you’d better be ready. There is no widget-interface, everything is done by left-clicking map tiles. It is everything you find in TBS games, contained in one screen and condensed playing time. It is easy to learn, entertaining to play, and beautifully executed. If you like the concept of Civilization but, like me, are loath to spend 15 hours or more on a game, then this may be for you. However, its strengths -tight focus and constrained game play freedom- are also its weaknesses: it gets “understood” fast and is quite repetitive. Technology comes in predetermined order, and due to the tightly defined game play, all games play out similarly. After the first hour, the game does not surprise you any more, but nonetheless, it is still enjoyable. Also, every game developer should study this game and so gain a better understanding of the mechanics of TBS games!

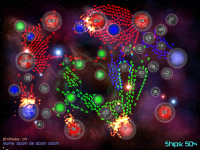

Imitation Pickles‘ Galcon – the answer to what you get when you try to reduce the RTS concept to the utter bare essentials, revealing the numeric attrition simulation underneath. You and your opponent start with a planet in a planet field. Your planets automatically produce ships, larger planets produce more. You can send an adjustable percentage of your ships to conquer other planets. That’s it. It is RTS gaming in its pure form, and is worthwhile for two reasons: one, it provides immediate and intense, though short-lived when you’ve learned it, action; and two, it is in effect a vivisection of the RTS concept showing the least common denominator for all games of the kind. Functional stylised graphics suitable for the game; minimalistic (again) functional interface that does the job, adequate AI that provides a challenge until you learn to beat it, after which the game lose replay value.

Imitation Pickles‘ Galcon – the answer to what you get when you try to reduce the RTS concept to the utter bare essentials, revealing the numeric attrition simulation underneath. You and your opponent start with a planet in a planet field. Your planets automatically produce ships, larger planets produce more. You can send an adjustable percentage of your ships to conquer other planets. That’s it. It is RTS gaming in its pure form, and is worthwhile for two reasons: one, it provides immediate and intense, though short-lived when you’ve learned it, action; and two, it is in effect a vivisection of the RTS concept showing the least common denominator for all games of the kind. Functional stylised graphics suitable for the game; minimalistic (again) functional interface that does the job, adequate AI that provides a challenge until you learn to beat it, after which the game lose replay value.